Garbage collection in C#

When you are programming, no matter the task on hand, you are manipulating some data. These are stored in basic types and objects and they live inside computer memory. Eventually, the memory fills up and you need to make more room for new data and discard the old one.

You can do it either by hand, like C and C++ programmers (used to) do, or use a languages with a mechanism that does it for you. In C# we are fortunate enough to have a garbage collector that takes care of our memory.

Basic concepts

In short, garbage collector tries to find objects that are no longer in use by the program and delete them from memory.

The first garbage collected language was LISP written by John McCarthy – one of the founders of artificial intelligence – around 1959. So the concept has been around for a while.

When you have a garbage collector in place you are making a trade off of safe memory allocations and programmer’s productivity for performance overhead. Garbage collected language will never be suitable for real-time critical applications like air traffic control, but you can get solid performance out of it – I’ve seen successful high frequency trading platforms written in C#.

Garbage collection is not only responsible for cleaning the memory and compacting it, but also allocating new objects.

.NET and CLR are making use of tracing garbage collector. That means that on every collection the collector figures out whether the object is used by tracing every object from stack roots, GC handles and static data.

Every object that could be traced is marked as live and at the end of tracing the ones without the mark are removed (swept) from the memory and it gets compacted. This is called a simple mark and sweep algorithm.

It gets a bit more complex than that but this is enough for having a simple mental model of what’s happening under the hood.

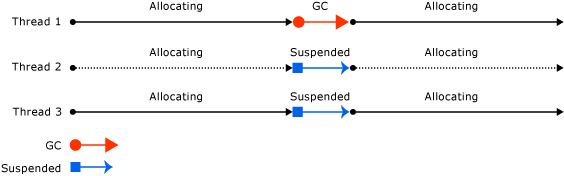

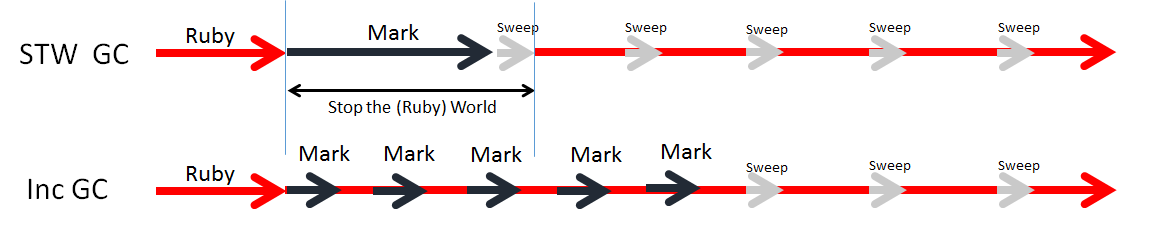

If the garbage collector halts the program when running we call this event stop the world. That guarantees that no new objects are allocated during collection, but it also means that there will be a delay in our program. To minimise that disruption incremental and concurrent garbage collectors has been designed.

Incremental collection makes the pauses shorter and works in small increments and concurrent doesn’t stop the program at all. For that you are paying with the overall longer collection time and the use of more CPU and memory resources than traditional stop the world.

Generational collection

In 1984 David Ungar came up with a generational hypothesis that layed the foundations of GC that are in use these days.

Young objects die young. Therefore reclamation algorithm should not waste time on old objects.

Copying survivors is cheaper than scanning corpses.

This hypothesis gave birth of the generational garbage collectors – first used in Smalltalk and used in all modern platforms today – C# is not an exception.

The memory is divided into several generations based on the age of objects. The collection happens in the youngest generation and the surviving objects are promoted to the generation above.

In C# we have 3 generations:

- Generation 0 is the youngest generation with short-lived objects in which the collection happens the most often. New objects are placed here with the exception of large objects that go straight to the Generation 2.

- Generation 1 serves as a buffer between the short-lived and long-lived objects.

- Generation 2 is the place for the long-lived objects and it gets collected less often.

When there is a collection over Generation 2 we call it full garbage collection as it goes through all objects in managed memory.

To keep the balance between generations most modern platforms are using a hybrid approach of generational cycles (minor cycle) and some variation of full mark and sweep (major cycle).

The CLR automatically adjusts itself between not letting the used memory get too big and not letting the garbage collection take too much time by setting thresholds for new object allocation.

The collection gets triggered when

- memory is low,

- threshold is exceeded or

-

GC.Collectis called manually.

When the collection is triggered every thread is suspended, so it can’t allocate new memory, and the GC thread goes into action.

As you already know the collector uses static data to know whether the object is alive or not. As the static fields are kept in memory forever (until the AppDomain gets unloaded) this might lead to a common memory leak when it refers to a collection and you keep adding objects to the collection. The static field keeps the collection alive and all the objects inside alive as well. Be careful about that and possibly avoid the usage of static fields if you can.

Characteristics

Modern garbage collectors have different characteristics and as with many things in programming – different trade offs. Based on the application requirements they could be tuned towards less interruptions and better user experience or maybe you want to run a fast server-side application that scales.

What characterizes a Garbage Collector?

- Program throughput: CPU time spent collecting vs CPU time doing useful work.

- GC throughput: amount of data the collector can clear per CPU time.

- Heap overhead: additional memory the collector produced during collection.

- Pause times: time needed for collection.

- Pause frequency: how often does garbage collection happen?

- Pause distribution: short pauses vs long pauses, and how consistent the pauses are.

- Allocation performance: how much time does the new object allocation take? Is it predictable?

- Concurrency: does the collector make use of multicore CPUs?

- Scaling: can your GC handle larger heaps?

- Warmup time: can a collector adjust to the characteristics of your application? How long does it take to adjust?

Configuration

You can influence the type and behavior of your application by setting garbage collection to a different type.

There are two major types – workstation and server. They could be configured by setting <gcServer enabled="true|false" /> element in your application configuration.

<configuration>

<runtime>

<gcServer enabled="true"/>

</runtime>

</configuration>

The workstation setting is tuned for client-side applications. Low latency is preferred as you don’t want your forms in WPF application become unresponsive during a long pause caused by garbage collection. In this mode it favours user experience and less CPU usage.

On the other hand, the server configuration is designed for high throughput and scalability of server-side applications and it uses multiple dedicated threads for garbage collection with the highest priority. It is faster than workstation but that also comes with more CPU and memory usage. This configuration assumes that no other applications are running on the server and prioritise the GC threads accordingly. Also, it splits the managed heap into sections based on the number of CPUs. There is one special GC thread per CPU that takes care of the collection of its section. You can run this mode only on a computer with multiple CPUs.

By default, the workstation GC mode is active.

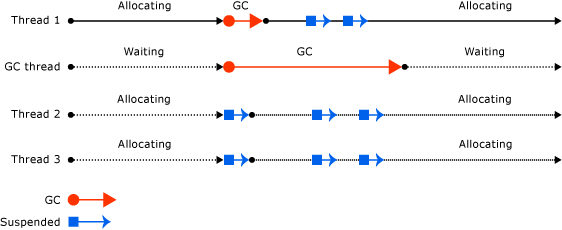

Another option you can choose is to use concurrent collection by using the <gcConcurrent enabled="true|false" />. It will give you more responsive application with less pause frequency and time.

<configuration>

<runtime>

<gcConcurrent enabled="false"/>

</runtime>

</configuration>

In concurrent mode, there will be an extra background thread that marks the objects alive when your application is executing its code. When it comes to collection, it will be faster as the set of dead objects has already been built.

The concurrency only affects the generation 2. Generation 0 and 1 will always be non-concurrent as they both finish fast and are not worth the extra overhead. When concurrent option is set, a dedicated thread will be used for collection.

To improve performance of several processes running side by side, you can try using workstation garbage collection with the concurrent collection disabled. This will lead to less context switching and therefore better performance.

Performance

The memory is divided into small object heap and large object heap. Large objects are the ones above 85 000 bytes and they go straight into the Generation 2.

In general, fewer objects on the managed heap is less work for garbage collector. That is applied especially to the large object heap that gets collected less often.

If you feel like GC causes you troubles there are various tools that you can use to debug it – memory performance counter, WinDbg or tracing ETW events.

Triggering collection manually with GC.Collect is usually more counterproductive than beneficial unless you really know what you are doing. It might help in certain situations when you want to release a lot of memory at once (e.g. a large dialog is closed and won’t be used again) – but unless you have diagnosed a memory problem, don’t go there.

If you are calling GC.Collect manually too frequently you will certainly see a decrease of performance in your application.

When you get into situation where the latency of your application is critical – like in the middle of the high frequency trading decision loop – you can set a low latency mode. This will put the GC into a low intrusive mode when it will become very conservative.

GCLatencyMode oldMode = GCSettings.LatencyMode;

System.Runtime.CompilerServices.RuntimeHelpers.PrepareConstrainedRegions();

try

{

GCSettings.LatencyMode = GCLatencyMode.LowLatency;

...

}

finally

{

GCSettings.LatencyMode = oldMode;

}

The collection of Generation 2 will be paused for the time in low latency mode. That leads to shorter and less frequent pause times and therefore decreased program latency. But that comes with the price that you might run out of memory if you are not careful. The best guideline is to keep those low latency sections as short as possible and don’t allocate too many new objects, especially on the large heap. In this case you might want to call GC.Collect where appropriate to force the Generation 2 collection.

Don’t forget that the latency mode is process wide, so if you are running multiple threads it will be applied to all of them.

Managed and unmanaged resources

In CLR all the code that is written is managed and it will be garbage collected. C# gets compiled into CIL and runs on top of CLR so all your C# code will be garbage collected.

That sounds easy enough until you need to use unmanaged resources.

And you will use them on almost daily basis as these are database connections, COM interops, network and file streams and many others. Unmanaged resources are not garbage collected and you need to free them from your memory by hand.

If you write a type that uses an unamanged resource you should

- implement the dispose pattern and

- provide a mechanism to free the resource in case consumer forgets to call Dispose.

The basic implementation of a dispose pattern with the use of SafeHandle could look like

public class DisposableResourceHolder : IDisposable

{

private SafeHandle resource;

public DisposableResourceHolder()

{

this.resource = ...

}

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (disposing)

{

if (resource != null) resource.Dispose();

}

}

}

To free the resource you can use Object.Finalize or SafeHandles. For more details check out Cleaning up Unmanaged Resources.

As a consumer of a type with unmanaged resource always use the using pattern.

using (var s = new StreamReader("file.txt"))

{

...

s.Close();

}

How can you tell the object needs to be disposed? It implements the IDisposable interface. Some static analysis tools can help you notice the cases where you might have forgotten to dispose your objects.

What about other languages?

The first versions of Ruby used a simple mark and sweep technique which isn’t the best performer but it was simple for the authors of C-extensions to write native extensions. That simplicity was the key to Ruby’s growth in the beginning and took it where it is these days. Generational collection was introduced in Ruby 2.1 (current version is 2.4) to improve the throughput of programs – quite late in terms of language maturity. After that Ruby 2.2 introduced incremental marking which addresses long pause times by running the GC in short increments.

Programmers in C++ don’t have any garbage collection and they need to do memory management by hand. There are techniques to make that easier – smart pointer are now part of the C++ 11 standard and are a tool that automatically deletes memory from the heap. Smart pointer can be implemented with reference counting that ensures that the object is deleted as soon as it is no longer needed – as opposed to tracing garbage collection when the unused object waits for the next cycle of collection.

Java is very similar to C# and uses tracing generational garbage collection – the heap is structured to a young generation (eden, S0 and S1), old generation and permanent generation. GC uses minor and major cycles to clean the generations and promote objects from one to the other. Both the collections of young and old generations are the “stop the world” event so all the threads are suspended until they finish. There are different types of collectors on JVM – serial, parallel, concurrent mark and sweep and its replacement G1 in Java 7.

Python doesn’t use tracing garbage collection but a reference counting with periodical cycle detection to solve the case of two dead objects pointing to each other. But as opposed to classic reference counting it combines it with the generational approach and uses the reference count instead of the mark and sweep algorithm. It doesn’t deal with memory fragmentation but tries to avoid it with allocating objects on different pools of memory.

In Javascript there isn’t a unified approach to garbage collection. It is in hands of browser vendors and they do it differently – Internet 6 and 7 used reference counting garbage collectors for DOM objects. From 2012 almost all modern browsers are shipped with tracing mark and sweep algorithms with some extra improvements – generations, incremental collection, concurrency and parallelism.

Conclusion

C# and languages on top of CLR are garbage collected. They use generational garbage collection with 3 generations and an advanced tracing mark and sweep algorithm to figure out which objects are still alive.

You can change the characteristics of the collector by changing to a server or workstation mode and setting up a concurrency mode.

Most of the times triggering garbage collection manually is not a good idea unless you really know what you are doing. And in cases where latency is important you can use latency mode to increase your program throughput and eliminate pauses.

Lastly, there are unmanaged resources like file streams, network, database connections that you need to take a special care of. Most of the times you’ll be implementing and using the IDisposable pattern so you don’t cause any memory leaks in your application.

If you liked this article you might enjoy C# Digest newsletter with 5 links from the .NET community that I put together every week.

Resources

- Garbage collection on MSDN

- Garbage collection on Wikipedia

- Tracing garbage collection

- Mike Hearn on Modern garbage collection

- David Ungar on Generation Scavenging

Comments

Justin Self: Nice Post. Minor note: Large objects (over 85,000 bytes) get collected during a Gen 2 collection but are not really part of the Gen 2. They are part of the Large Object Heap.